Home » COVID19 as Seen Up Close

COVID19 as Seen Up Close

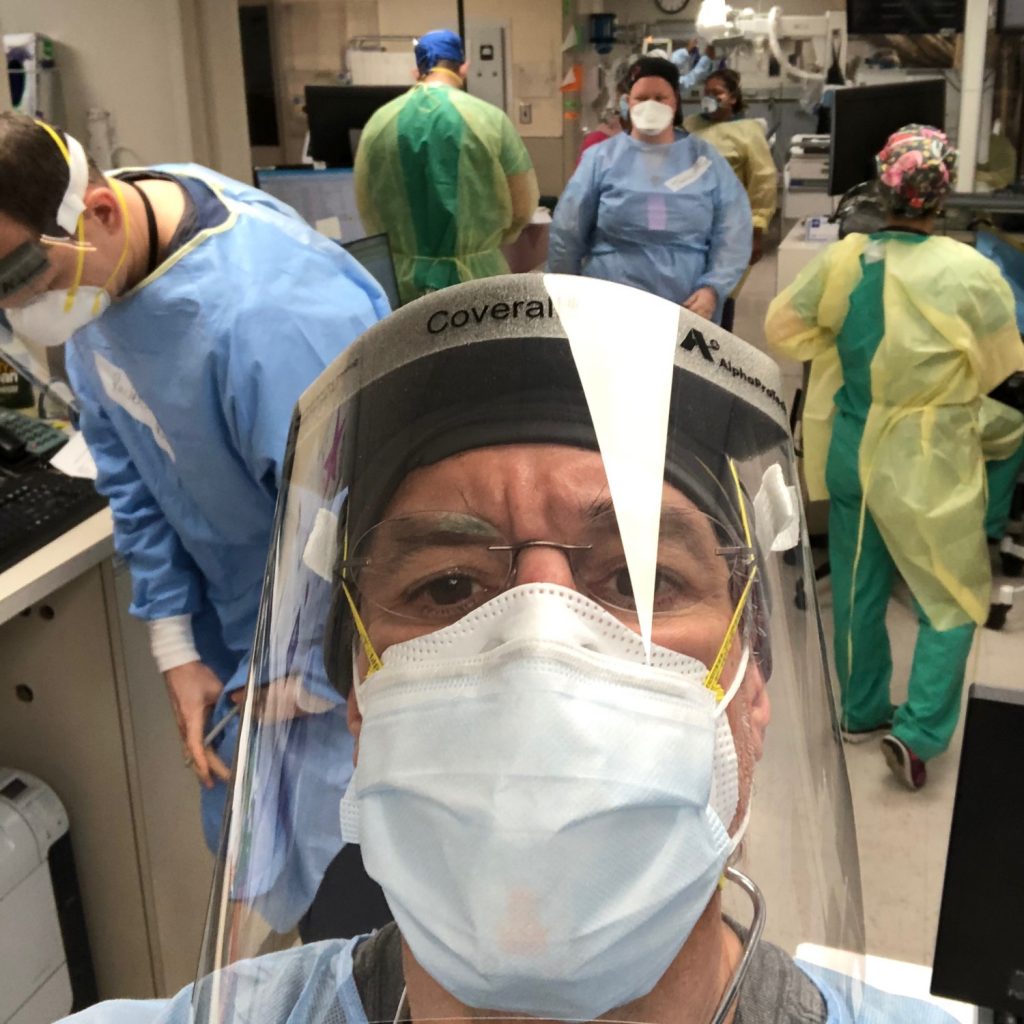

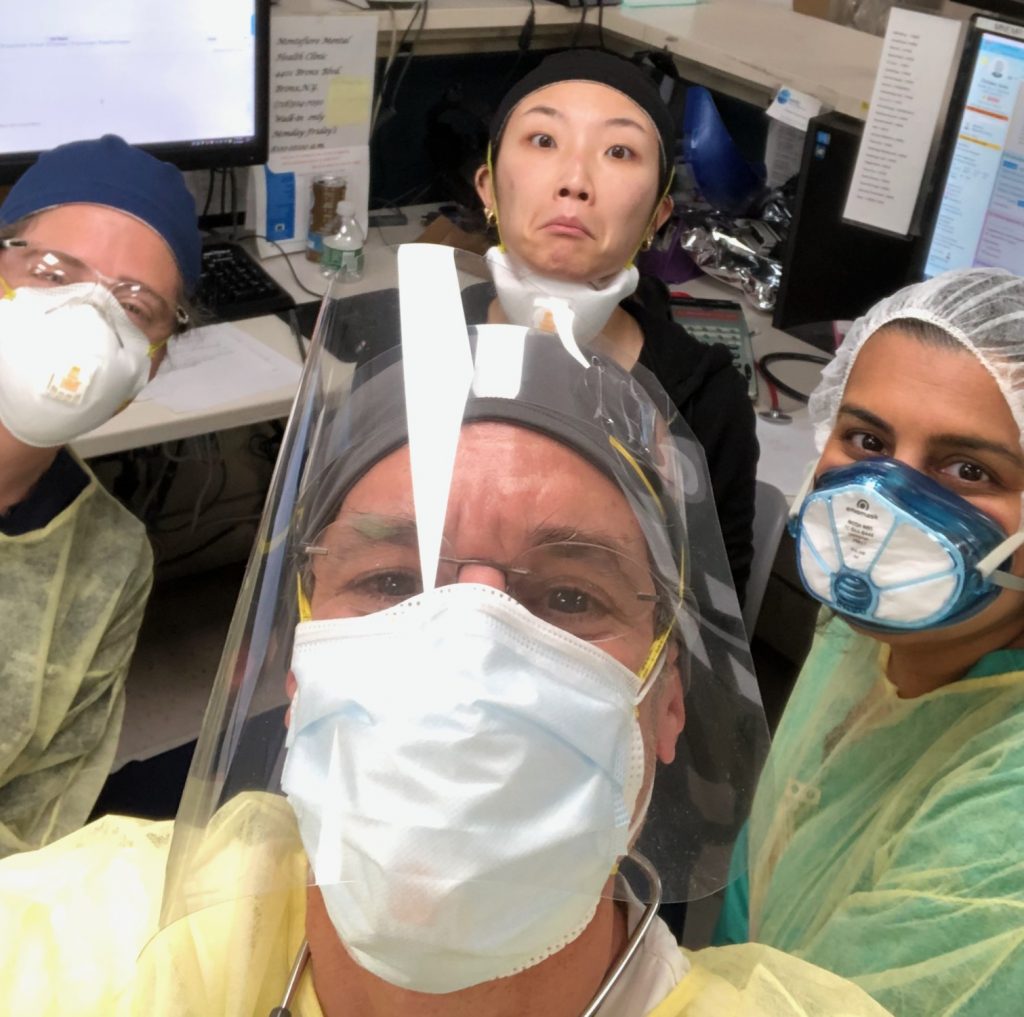

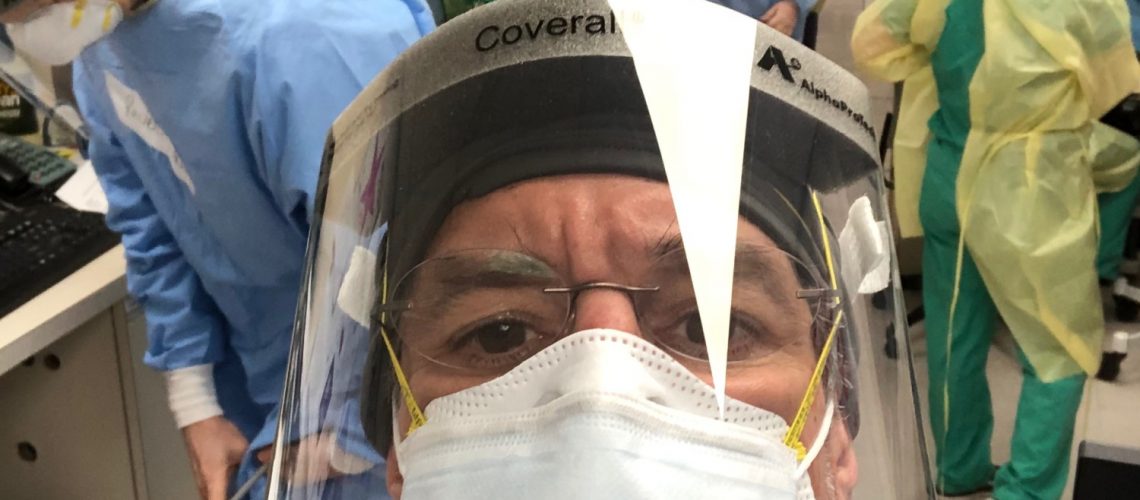

That, of course, is among the lesser lessons of my very brief stint lending modest support to colleagues on the front lines. But though relatively unimportant, it was indelible just the same. Wearing dual masks and face shield for 12-hours changed nearly everything about the feel and flow and rhythms of an ER shift- rhythms I remember well from the early days of my clinical career.

We all had sore noses, heads, and ears from elastic bands and mask pressure. We all had a hard time hearing one another clearly. Meeting new people, knowing who was who, was very challenging with faces covered and everyone in the same generic gowns. Names on a strip of tape across the chest were most welcome. Patients, often short of breath to begin with, all sounded terribly muffled. We said “what?”- and they responded “huh?” Such dialogue does not a great medical interview make! I totally believe- as Jay Leno suggested on Real Time with Bill Maher– that “are my test results back?” could readily be received as: “are my testicles black?”

And, the simple, sustaining rituals of ED life were all but impossibly inconvenient. I did manage a cup of coffee once- but the need to un-gown, go get it, re-gown, and then work around the masks to sip my way through it- made it a very close value call. The caffeine was most welcome with my 5AM wake-up times, but was it worth the trouble? Just barely.

OK, enough of the intimate banalities- on to the big picture.

During those 36 hours in the emergency department, it was perfectly clear how massively COVID19 has disrupted health in this moment. Almost no matter what symptoms or complaints brought people to the hospital, inevitably- they had COVID19. Those who didn’t have it, whether in with related or unrelated symptoms, serious or minor, were the exception. In this moment, COVID19 is the rule.

But it was not one disease- it was, at a minimum, two. Among the already sick and elderly, many sent in by ambulance from nursing homes, COVID was serious, ominous, and all too often lethal. But to be blunt about it, this was much the same demographic that routinely populates a busy emergency department, the same population prone to acute and serious illness and death. Many of the people I saw dying of COVID were the people one regularly sees dying in the ER- but of sepsis, or pneumonia, or myocardial infarction, or stroke, or heart failure, or renal failure instead. COVID is, effectively, consolidating a mortality toll that would have played out over some number of weeks and months, making it all happen now, and for one primary diagnosis rather than many. I will even go out on a limb and make this prediction: all-cause mortality for the remainder of the year after the COVID crest comes and goes will be lower than usual, because the disease is mostly accelerating death in those already most proximal to it.

I hasten to note that does not attenuate the tragedy of this. For one thing, those extra weeks, or in some cases months, could mean a lot to a given patient, and perhaps even more to their families. For another, families can’t come to the hospital now- so these losses to COVID deny the comfort of loving company that is the essential means of going gentle when the light dims that final time. Dying is inevitable, but dying alone is inexpressibly sad. Among the many reasons I hate this contagion, I hate it most for that dreadful consequence.

COVID, though, is another disease altogether among the generally young and generally healthy. Almost all of the doctors I was working with have had it and recovered. Some tested positive, quarantined as required, and are now back. Some, never tested, may have inadvertently or otherwise worked straight through it. But by one path or another, they have mostly been through this disease, and generally found it to be mild. So, too, for most of the other health professionals making up the elaborate choreography of a busy emergency department.

Going toe-to-toe with COVID daily, and in so many cases having suffered the illness themselves, you might think front-line health professionals would reliably fall in the “let’s keep everything strictly locked down” camp, but from the many conversations I had- you would be wrong. Bear in mind, doctors, nurses, techs, clerks, orderlies, paramedics…are all, actually, people. They all live in the world, and are subject to the conditions of it.

So, the doctors working their long and intense shifts spoke with comparable passion about the challenges of balancing that with home-schooling their children. They want, and need, and favor a proximal return to educational normalcy. The many health professionals with siblings, in-laws, other family, close friends now laid off, furloughed, or otherwise unemployed- were massively preoccupied by such concerns. They are on the front lines of health care, but care as much about loved ones on the front lines of other disasters: the inability to pay rent, or put food on the table.

And, of course, there are insoluble conundrums in the mix, too. When Dad is a nurse, and Mom is a paramedic, and they have young children at home and no recourse to any of the usual means of caring for them- it means one of these crucial, front-line professionals must stay home. Taking care of one’s young children is never optional.

So it is that the view I encountered- in an emergency department, in a hospital, in the hardest hit part of the hardest hit state in the hardest hit country to date- was not extreme. It was centrist. It was: we need to balance how we confront the clinical toll of this virus with how we contain the rest of its ruinous fallout. When I talked to them about “vertical interdiction,” eyes, generally, did not roll; heads nodded.

From the start of all this, we have languished in the realm of the opposing, but comparably preposterous. It is preposterous to say “everyone back in the water, including grandma and grandpa, and never mind the rip tides and sharks…” That is what an indiscriminate campaign to “liberate” a state sounds like to me. It is heartless, thoughtless, and callous. But, so, too, is “hunker in a bunker on an indefinite timeline until there’s a vaccine or you die of something else, whichever comes first.” So, too, is inattention to the possibility that poverty and hunger will kill many more people- perhaps even orders of magnitude more people- than infection.

The ED I worked in had pictures up on several walls of a beloved nurse, relatively young, and with a beautiful smile- who died of COVID. When I spoke to one of the docs about her, she teared up and couldn’t speak. No decent person can be dismissive of such excruciating cost.

But we cannot ignore the tale of scale, either, told in facts and figures rather than expressions on a familiar and loved face. They tell us now, as they told us early on, that risk of severe infection varies markedly, and that for those at lower risk, there is greater likelihood of ruin from haphazard interdiction than from infection- while just the opposite is true for those at high risk.

We need representative, random sampling– and we need it yesterday– to corroborate what appears to be true: that infection in the U.S. was far more widespread than we’ve documented, and that we may already be well on our way to the collective protection of herd immunity that gives us all our lives back.

As best I could tell, the intimate, poignant perspective of the front line belies the false allure of opposing extremes and lends support to the objective of #TotalHarmMinimization. As best I could tell, right where COVID19 is seen up close and most intimately, the case for a middle path through the big picture consequences of all this prevails.

-fin

This article was first published on LinkedIn.