Home » NOTeD on Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Weight Gain Versus…

NOTeD on Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Weight Gain Versus…

Well, the Weight of Evidence

The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model

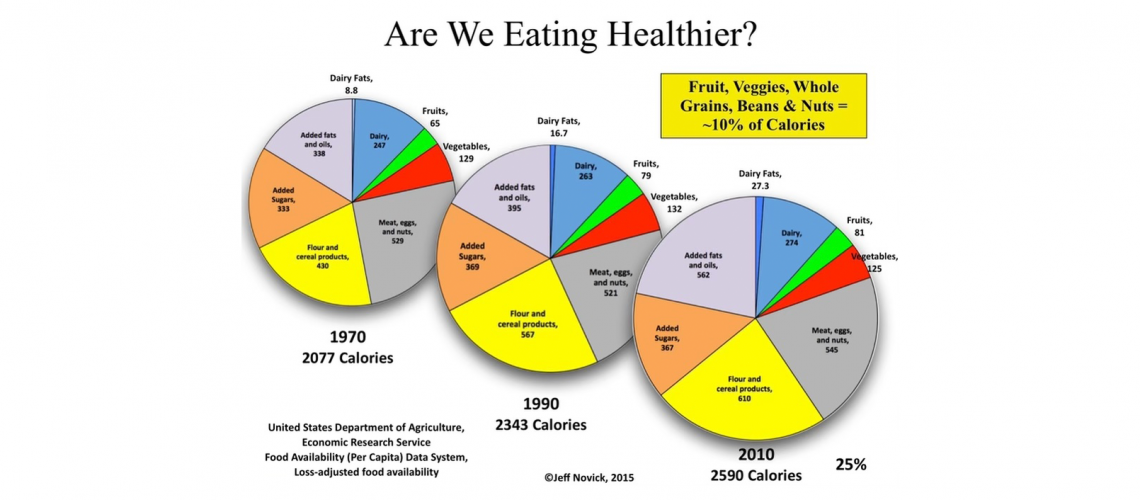

The irony is glaring that the CIM argues calories are not important while concomitantly arguing that intake of highly refined and processed carbohydrates leads to increased calorie intake. The model appears unable to accommodate the fact that intake of excess calories from fats, alcohol and protein can contribute to metabolic obesity and insulin resistence in their own ways as well.

The distilled truth is that calories absolutely matter.

And CIM proponents, while arguing calories don’t matter – their “cake” – contend that the end result of refined carb intake is increased hunger leading to increased calorie intake. So they are having their cake and eating it too. It is a circular, self-defeating argument with clear weaknesses even in its core contentions. And it’s notable CIM proponents often do little to differentiate jellybeans from actual beans. Nevertheless, that calorie rich, refined and highly processed (CRRAHP) food mitigates hunger less is a reasonable contention, but one inconsistent with saying that calories don’t matter.

Highly refined and highly processed calorie intake – whether carbohydrates, fats or alcohol – decreases the likelihood of the following:

- The “ileal break” based reduced appetite: A phenomenon manifests when residual food stuffs traveling through the digestive system are yet to be absorbed at the end of the 20-25 feet of small intestine – this final segment called the ileum. The phenomenon is called “ileal break,” a benefit of regularly eating intact fiber-rich foods. Such foods, when passing through the ileum, will effect a reduction in appetite. These foods are antithetical to the low carbohydrate approach beyond low-starch vegetables: whole fruits, root/“starchy” vegetables, legumes such as beans, lentils and peas as well as intact 100% whole grains like steel cut oats, and many more.Dietary patterns utilizing intact fiber-rich foods – which are consistent with the longest living populations on earth called “Blue Zones” – allow residues of foods to make it all the way to the ileum and result in increased ratio satiety-to-hunger hormones; ie, the ileal break.

Foods absorbed quickly and early in the small bowel due to their lack of intact fiber – whether they are fat-free SnackWells or fat-laden potato chips – do not offer an ileal break benefit. So yes, CRRAHP carbs can result in less appetite control than high intact fiber-based foods or even protein rich foods. But the same is the case with CRRAHP fats such as excess oils and butter. And the problem is cutting out fiber rich forms of (appetite-controlling) carbohydrates that are consistent with longevity. - Gut Microbiome. Appetite suppression from short chain fatty acids produced by healthy gut microbiome fueled by a variety of intact fiber sources, which may even mitigate some calories being absorbed from calorie dense foods.

- Highly Intact Plant-based Foods. The phenomenon that eating more highly intact plant-based foods results in fewer calories from those foods being absorbed and a calorie only counts if it is absorbed in the first place.

So, with condolences to the “carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity” enthusiasts: the first law of thermodynamics is as intact as fiber from steel cut oats, and calories absolutely do count. And yes, the sources from which calories are derived do lead to the phenomena above in which less of them are eaten and/or absorbed (usually a mix of both).

On a final note, even highly processed calories could be consistent with less disease if they could be controlled. Primates in the University of Wisconsin longitudinal study were provided the same highly refined and processed based “chow” (processed carbs, proteins and corn oil for fats), but 30% less in the calorie restricted group (who are notably voraciously hungry at breakfast and often irate, presumably from being “hangry”). The calorie restricted (and caged) group still manifested remarkably lower rates of cardiometabolic disease and aging vs the unrestricted chow cohort.

Unlike the monkeys in the University of Wisconsin long term project looking at calorie restriction and longevity in primates, we cannot be simply placed into cages and forced to eat less CRRAHP foods. Humans are in a free-living, ad libitum, environment. Anyone for living in cages? Or would you like to give more whole fruits, whole intact grains, beans, lentils and peas a try?