Home » Of COVID, Testing, Case Counts, and Waves

Of COVID, Testing, Case Counts, and Waves

Having been bowled over and tossed around by the COVID wave here in the Northeast, my heart goes out and my best wishes extend to the individuals, families, and health professionals buffeted by that rough surf in other parts of the country now.

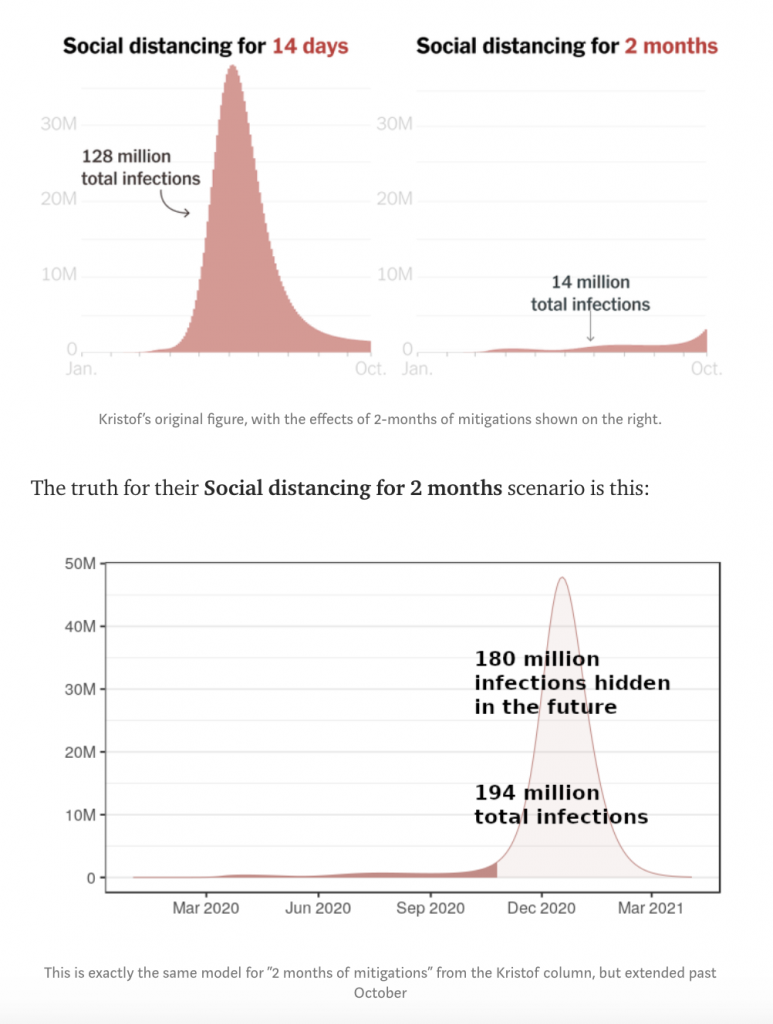

This is, sadly, as predicted. Professors Chikina and Pegden projected what is now happening with haphazard reopenings using the very mathematical models invoked to argue for flattening the curve. Flattening the curve was one of the reasonable options for phase 1 of the pandemic response, but as their modeling clearly showed- could never be more than that. The reasons are rooted in the powerful forces of biology.

Image from: A Call to Honesty in Pandemic Modeling; Chikina M, Pegden W. Medium. March 29, 2020

Infectious diseases of all sorts, however malevolent they may seem because of their effects, are simply organisms looking for places to reside, find sustenance, and replicate. They follow the imperatives of all life, in other words. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 in common with all other human pathogens, our bodies represent such a place. The virus is no less “committed” (this is in a strictly biological sense, of course; not in any “thinking” sense) to seeking us out than any of us would be to finding shelter, food, and water in need. The virus, if in the environment, will never stop seeking.

A short set of factors determines the consequences attached to this fraught game of hide and seek. First, the properties of any given pathogen dictate how effectively it travels from host to host, and how readily it evades a host’s defenses to establish itself within. SARS-CoV-2, transmitted primarily via water droplets through the air, travels with moderate efficiency (the Ro)- more than influenza, far less than measles. It handles our defenses with moderate efficiency as well.

The next consideration is dose, a much-neglected topic. The best way to think of dose, or number of viral particles in a given exposure, is like an assault by an enemy force on a compound you are defending. Your body is the compound, your immune system is your defense force, and the virus is the enemy. If the enemy are few, you repulse them with little effort and no harm. If more, you repulse them- but with considerable effort, and some potential harm. If their numbers are vast, they are apt to overwhelm you. That first scenario is a tiny exposure to COVID19, unlikely to produce symptoms. The second is a symptomatic illness. The third is a bad case of the disease and possible death. Dose matters.

And, finally, there is us- and the rigor of our native defenses against this home invasion. As has become abundantly clear in the months of this pandemic, young, healthy people repulse this enemy far more effectively than the elderly, the frail, and the chronically ill. Being in good health before COVID finds you, other things being equal, makes an enormous difference to the probable outcome. Overwhelmingly, COVID19 deaths and complications have been concentrated among older, chronically ill people. Bad bouts in young, healthy people are quite rare – despite the impression left behind by relentless news coverage of the “if it bleeds, it leads” variety that has made them seem otherwise. When they occur, as they have in health professionals on the front lines, they are often associated with very high exposures.

The other critical determinant of our self-defense is, of course, immunity. I see indications of, and mechanisms have been published for, a fairly widespread, partial immunity to SARS-CoV-2, probably owing to prior exposure to other coronaviruses. It appears that if exposure levels are ordinary rather than intense, more than half of all people exposed to this virus- even as many as 80% of us- do not tend to get infected. Of those who do, a sizable portion- the estimated percentage keeps changing, so let’s not bother being too precise- have no symptoms. Most of the rest have mild symptoms. The highly vulnerable, epitomized by our loved ones in nursing homes, are prone to devastating illness.

Whether or not this virus will wane with the seasons to wax again when they change is a matter of pure conjecture; no one knows. (My hopeful conjecture is: no. But hope is not a strategy, and we’d best be prepared.) It is possible that case counts will decline in summer, and spike again in the fall. This has happened with past flu pandemics. Were case counts to spike again in New York City, or northern Italy, that would be a genuine second wave- because these, clearly, are populations that have been bowled over by a first.

What is happening in much of the United States now is not a second wave. It is just the release of the first wave, pent up during the lock down.

Testing does not explain the spike in cases in Texas and elsewhere. Of course, if we test more, we will find more cases, assuming there are cases to find. That is a good thing. Knowing how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 is essential to our understanding of everything from the fatality rate to resource requirements, and we are stunningly in arrears with regard to such fundamentally important data. We continue to guess at the true fatality rate for COVID, because we do not reliably know the denominator: the total number who have been infected in the first place.

You can only know that number by going out and looking for the mild cases that do not present for medical care. Since the global data suggest that the overwhelming majority of COVID cases are mild, more testing should reveal more cases. But if more testing is just finding cases that were already there, it will not be associated with a rise in hospitalizations, or deaths.

There are two ways to know that a surge in apparent case counts is real. The first is to observe a rise in cases once a high, constant level of testing is established. If the percent of a given population subject to testing stays the same, and the percent testing positive goes up, that is a real spike. The other way is to observe a trend in effects that are never overlooked. We do not tend to miss it when people require a hospital bed, or the ICU. When these are trending up, it is a real pandemic wave. So it is now in Texas.

Our federal leadership has suggested that if we want fewer cases of COVID, we should simply do less testing. Nick Kristof has provided the best rebuke of this nonsense I’ve seen: it’s like saying if we stop filling out death certificates, no one here will ever die.

Cases of COVID are out there, or they are not. If they are, knowing about them is a good thing. Finding more cases might even be good news. The more undetected, mild cases we find, the more it lowers the rates and risks of severe cases and fatality. The higher the proportion of us shown to have encountered this virus already, the greater the prospects for herd immunity, and a return to something like life as we formerly knew it, not dictated by the timeline of vaccine development. More testing means more knowledge, and more knowledge means more power over our pandemic destinies. Bring it on!

Testing more will mean finding more cases so long as the virus is in circulation. Finding more cases without a concurrent rise in severe cases will help us better gauge the true risks of infection, by building a better denominator. Finding more cases as hospitalizations rise in tandem tells us our policies are failing, invites us to revise them, and helps guide estimates for the resource requirements (e.g., hospital beds) required to compensate.

Our policies in the United States are clearly failing, but we are not alone. Every place around the world that locked down indiscriminately now faces the same peril- a delayed first wave of COVID- if they open up just as indiscriminately. The force of a pent-up viral wave will not be denied. How, then, can it be handled- short of staying in lockdown until the advent of a highly effective, acceptably safe, mass produced, universally distributed vaccine?

By means of well-informed risk stratification. If we think of pandemic waves as actual waves, a quite helpful vision ensues. Young, strong, healthy people who can swim- are apt to ride out a rough wave just fine. The elderly and frail should stay out of that surf.

But there, the analogy breaks down- because able swimmers in rough surf do not cause the surf to quieten. In the case of contagion, however, they do just that. When enough of us who can safely overcome COVID exposure have done so, we become the wave break of herd immunity. We make the water safe for everyone.

In short, the right way to avoid both disastrous waves of contagion and the duress of extended lockdown, is for us to return to the world in waves of our own, based on risk stratification. Opening up with the lowest risk populations first is the safest way to “test the waters” where we are unsure about levels of viral circulation. But a “we’ve lost our patience, everyone back in the water” approach is a costly mistake. That cost is being tallied right now in crowded hospitals from Houston to Tallahassee.

Places that have experienced a genuine first wave of COVID may or may not encounter a seasonal, second wave; we can prepare for that, but have no direct control over it. We can, however, and certainly should, ride out the wave we are already in far better than this. We don’t need to stay in lockdown, but the alternative cannot be “everybody in the water, never mind the riptides and whether or not you can swim.” Some of us can safely ride such waves; those who cannot should be protected from them.

Now, as at the start of all this, it seems clear that the route to total harm minimization requires us to respect the virus, even as we recognize the quite variable risk it poses to different groups among us. We can counter the threat of waves of contagion by returning to the world in waves, responsive to that variable risk.

The more testing we do, the better we measure, and the more prepared we are to manage, those risks. Testing is scanning the horizon to see what waves are out there. Failure to test does not stop the waves; it simply means we await them with our heads in the sand.

-fin

This article was first published on LinkedIn.