Home » As Cities Move Toward Reopening, How to Manage Risks

As Cities Move Toward Reopening, How to Manage Risks

Which brings us to now — where we understand that for everyone, there is a need to balance their hunger to participate — whether in work, protest gatherings, or other events — with the realities of their health and safety. But that can be a challenging calculus. With that goal in mind, here then is an attempt at some quiet clarity — on both a population level, as well as to help individuals make their own choices.

In Phase 1, the collective goal was to hit pause on viral transmission, “flatten the curve,” and avoid an overwhelming demand on the medical system. To the extent this worked, we bought the health system time to prepare and learn about this virus and the best — and often entirely unexpected — ways to treat it. We avoided infections that might otherwise have occurred and saved lives.

However, the same efforts also led to economic hardship, mass unemployment, and societal disruptions unlike any most of us have known in our lifetimes.

We are now headed into Phase 2 — whether by careful consideration or mere impulse — where restrictions are loosened. This is already happening, so debating the prudence of it is rather moot. The right question about an inevitable process is: how should we manage it? What are our goals, and what are the best ways to achieve them?

First, the quantification of harms in any direction, and the potential tradeoffs in efforts to minimize them all — are data-dependent. Policy decisions will be made in a partial fog at best until representative random sampling of the U.S. population for infection and immunity is completed. This is long overdue.

Along with securing the requisite data, we propose two tactical priorities. The first is infection risk stratification; the second is exposure dose management. Together, these can inform the policies, programs, and personal behaviors of Phase Two, even with the limited data we now have.

Risk Level

We now know reliably that Covid-19 does not strike everyone with the same severity. Age is a salient risk factor for severe disease; baseline health also exerts a major influence.

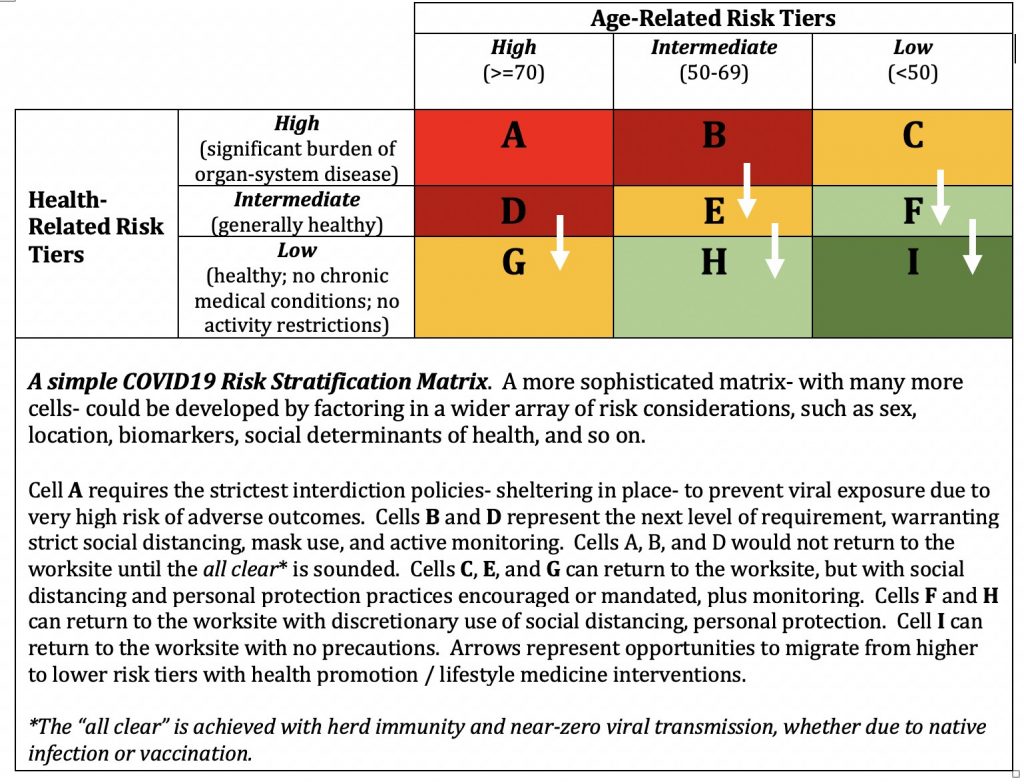

The matrix below illustrates the risk of a bad outcome from Covid-19 infection in relation to age and general health status. Cell A represents the highest risk population, while Cell I represents the lowest risk group. White arrows indicate opportunities for individuals to reduce their risk by improving their health.

Risk-Stratification Matrix

There are many ways to more precisely risk-stratify, including the presence of various medical conditions, management of those conditions (e.g., poorly controlled diabetes or hypertension increases risk relative to well-controlled); and behaviors (e.g., smoking), gender, location, and social determinants of health. However, the general concept is simply that protection against viral exposure — for both policy and personal practices — should vary with risk tier.

This, in turn, invites considerations of dose.

Exposure Dose

Per the famous quotation by Paracelsus, “the dose makes the poison.” This is true for pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, as well as potential toxins.

To understand why, consider this metaphor — you are guarding your compound and are stormed by an enemy. If this assault is by a small, haggard band (low exposure dose)- you can fend them off with no or minimal damage. But if you’re swarmed by a large army (high exposure dose), you’re far more likely to sustain damage and risk being overthrown.

Your body is the compound; your immune system is your defense force — and in this case, the viral particles of SARS-CoV-2 are the enemy.

Exposure dose determines whether you get sick (since a certain threshold of viral particles is required to create infection); it’s also likely that exposure dose is one factor (of the many) in determining how sick you get, once that threshold is met.

We are still learning the details of this new germ, but we have prior knowledge on which to draw. In research on Tuberculosis, inhaled dose correlates with disease severity. Similarly, a study of a SARS outbreak in an apartment complex showed that those who lived closest to the index patient had higher viral loads. While most cases of Covid-19 in young, healthy people have been mild/moderate, there have been some deaths — including in young, otherwise healthy medical professionals. The difference in cases of medical professionals was likely a massive exposure dose related, for instance, to the performance of procedures, such as intubations and bronchoscopies among critically ill patients expelling large numbers of viral particles.

Thus, the relevance of exposure dose, little-discussed to date, suggests that as restrictions are loosened and the population is inevitably exposed to Covid-19, even the healthiest among us should be exposed to the lowest dose possible, potentially lowering risk of any illness, and/or severe illness. Exposure dose management is one among the important means of advancing toward the all-clear of herd immunity with minimal hardship.

One caveat: while this proposal is based on population-level trends, there are always individual outliers. Situations such as super-spreaders (otherwise healthy individuals who are highly contagious) present an unpredictable variable, particularly in large gatherings.

Thus, to move forward, the most powerful strategy is a combination of individualized risk stratification and exposure dose management.

How to Determine Risk

Highest risk groups (A): This group requires the most strict, most meticulous protection — and sheltering in place to prevent exposure entirely.

Groups B and D represent the next level, warranting strict social distancing, mask use, and active monitoring. A, B, and D would not return to the worksite until the “all clear” is sounded.

Groups C, E, and G can return to the worksite, but with social distancing and personal protection practices encouraged or mandated, plus monitoring.

Groups F and H can return to the worksite with recommended social distancing and personal protection.

Group I, the lowest risk group, is young people in perfect health. For this group, there is now a mindset shift: the goal is no longer one of total avoidance, but to manage the probability of exposure — and exposure dose — if exposure occurs. As that creates many gray areas and questions, we propose using the 4-factor framework below to gauge the exposure *DOSE* of various activities. Group I may start to resume many daily activities but should manage activities to minimize exposure dose.

Factors Driving Exposure Dose

- Density: How many people are in one place, and how closely? What is the density of your city or of a chosen activity? Volume of airflow directly impacts infection risk and explains why a crowded bar/concert/movie theatre significantly raises risk. While being outdoors may mitigate risk, crowds themselves present an inherent risk, especially if densely packed.

- Degree of activity: Activities with loud speaking or intense physical activity all increase the risk of transmission, as seen in infections after choir practice in Washington State, or in group exercise classes in South Korea where a single instructor led to an outbreak of 112 individuals. Singing, shouting, exercising — each of these carry additional risk.

- Duration: Probability of infection is directly linked to duration of exposure. Living in the same house with someone who is acutely ill is high risk, while just a quick pass-by on a street is much less so.

- Distance: We all know the 6-foot rule — but let’s be clear: there is no law that COVID cannot cross 6 feet. In some instances, germs can travel 10 and even 20 feet. Meaning that the 6-foot rule is a useful guideline but no panacea.

Putting it all together, a situation in which all 4 factors were high risk would be a HIGH DOSE event, whereas one where all four were low risk would be a LOW dose event. Protests, large community gatherings, conventions — these all represent high dose events and carry with them concerningly higher risk of spread.

Of course, when high and low-risk groups interact, the low-risk individuals must accommodate the requirements of the high-risk. For instance, a lower-risk individual who has participated in higher dose exposure activities should isolate themselves from a higher risk individual for two weeks. Separately, that also includes wearing masks — a low-cost but high-yield habit — when we are among higher-risk persons, or in any high-dose event.

Because many of the risk factors for bad Covid-19 outcomes are modifiable, and long-term drains on human vitality and national productivity alike– there really never has been a better a time for a national health promotion campaign. Accommodating risk tier is good; lowering that personal risk, and migrating to a lower tier- is obviously better.

The details of what lies ahead won’t necessarily be easy, but a basic understanding of the priorities is fairly simple. Per what has become a pandemic aphorism- we are all in this together. We do not, however, all face the same risks. Phase Two will best serve the goal of risk and dose minimization if we advance to it in common cause, while recognizing, honoring, and accommodating our important differences.

This article was first published on Medium.